Viggo Mortensen arrives on time at the touristy Chart House restaurant off L.A.’s Pacific Coast Highway. His cheeks are pink from sunburn; his hair is slicked-back and wet. He has the relaxed air of someone who has spent the day outdoors being reminded of life’s immensities—the sea, the desert—and is relieved to have been reminded. Mortensen is a dirty blond with a triangular jaw; from afar he resembles a taller, cleaner Kurt Cobain. He also shares Cobain’s intensity—a quality that leaves him seeming a bit wounded, a fragile flower. Today, his melancholy trickles in from memories of New Zealand. He has just returned to the States after living there for more than a year while filming the Lord of the Rings trilogy, an epic filmmaking tour of duty that had the actors shooting three films back-to-back on a rigorous schedule.

Viggo Mortensen arrives on time at the touristy Chart House restaurant off L.A.’s Pacific Coast Highway. His cheeks are pink from sunburn; his hair is slicked-back and wet. He has the relaxed air of someone who has spent the day outdoors being reminded of life’s immensities—the sea, the desert—and is relieved to have been reminded. Mortensen is a dirty blond with a triangular jaw; from afar he resembles a taller, cleaner Kurt Cobain. He also shares Cobain’s intensity—a quality that leaves him seeming a bit wounded, a fragile flower. Today, his melancholy trickles in from memories of New Zealand. He has just returned to the States after living there for more than a year while filming the Lord of the Rings trilogy, an epic filmmaking tour of duty that had the actors shooting three films back-to-back on a rigorous schedule.

“I loved being there,” Mortensen says, his voice surprisingly high, almost Chet Bakerish. “We got to see places that even most New Zealanders haven’t seen. Native beach forests that have never been touched and look like they did 1,000 years ago. It was easy to believe we were in some magical place. I can imagine living there…but I can imagine living in a lot of places.”

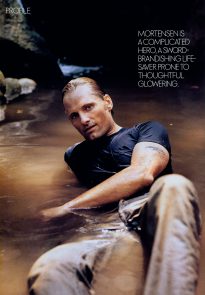

Mortensen is a drifter—he’s lived in several locales, South Americia and Denmark included—and finds settling down problematic. He approaches his career with the same ambivalence. Now forty-three, Mortensen has been acting professionally since 1984. He has scored small roles in more than twenty-five films, playing his characters memorably without seeming to say, “Hey! I’m puttin’ on a show here!” Range is not a problem: He has portrayed everything from the Devil (in The Prophecy, in which he rips out Christopher Walken’s heart and takes a nibble) to the other man (in A Perfect Murder and A Walk on the Moon, in which he rips out Gwyneth Paltrow’s and Diane Lane’s hearts, but not before they nibble on him). Now, playing Aragorn in the J.R.R. Tolkien trilogy directed by New Zealander Peter Jackson, which debuts this month with the highly anticipated The Fellowship of the Ring, he has at last been cast as what he so clearly seems destined to be: a complicated hero, a sword-brandishing lifesaver prone to thoughtful glowering and full-body, romance-novel embraces—long hair seductively askew, lips parted and moist with purpose.

“I’m one of two humans in the Fellowship,” which includes a wizard, four hobbits, an elf, and a dwarf who team up in a quest to destroy a magical ring, he explains. “It was the best team I’ve ever worked with, like a family, the unity we had.” To celebrate their bond, the Fellowship decided to get identical tattoos—the number nine in Tolkien’s fantasy language. Even Sir Ian McKellan got inked. “He was into it,” Mortensen says animatedly. “It’s the only tattoo he has.”

Despite the closeness he forged with his fellow actors, including Orlando Bloom and Elijah Wood, Mortensen shuns the Hollywood life, preferring the isolation of Idaho, where he is building a house. His top priority is raising his son (with former wife Exene Cervenka, lead singer of the punk band X), Henry, thirteen. “Henry keeps me honest,” he says proudly.

Mortensen is big on honesty. He calls himself not a movie star but a “working actor with a long shelf life.” He is also an artist—in that obsessive, uneasy-in-the-material-world sort of way. He paints: explosive art brut canvases layered with color and snippets of text. He’s published a book of poetry. He takes evocative photographs of truck beds and Barbies. He does not photograph or paint pictures of himself. He does not read his own press. Refreshingly, he has little interest in his own image.

“I look at all art as the same thing. With acting, if you’re not getting something out of the moment, you’re not there. If you’re on the cell phone in your trailer, mapping your career, saying, ‘I want that role because it might get me an award,’ then you’re not paying attention to the rain or to a crew member’s broken leg. Those things mean more to me than success.”

What a rarity: an actor who finds other people more compelling than himself. He is also an actor who picks up the check, who writes thank-you notes, and who, when terrorists attacked New York one horrible day in late summer, called to console a journalist he’d known only for a couple of hours.

“I feel like what we talked about was so trivial and stupid now,” he lamented on the voicemail recording, his little voice barely audible. “I hope you’re okay. I’ll try again later.”

Back at the Chart House, before the world was coated with loss and dread, Mortensen is lighthearted, his thoughts returning to the Fellowship.

“The movie is about doing the right thing for its own sake, not for any reward.” He drains his glass of wine and smiles. “Traveling is always better than where you’re going. Otherwise, what’s the point of living?”