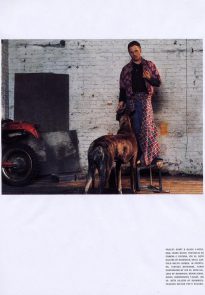

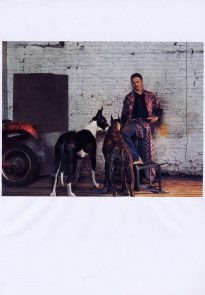

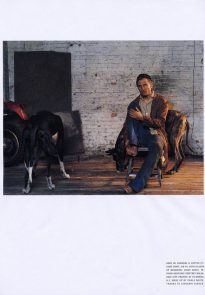

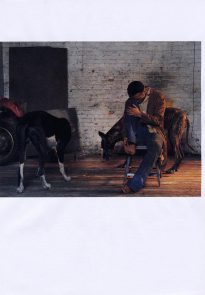

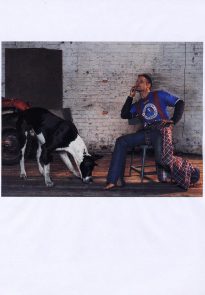

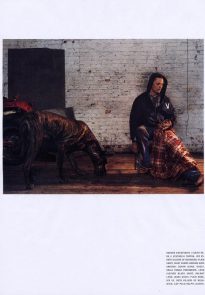

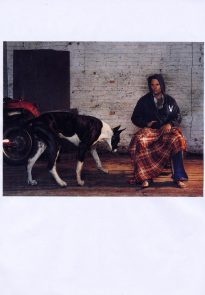

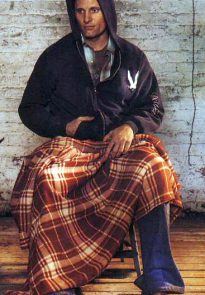

A February Sunday’s report begins in a Brooklyn hangar and ends in a small airport North of New York. In between lay five hours of shooting that pass quickly while he goes back and forth from a trailer, silent and reserved, cigarette in mouth, no shoes on (he feels comfortable barefoot), in his hand – the typical wooden cup of mate, a very popular drink in South America. “Do you drink it too?” he asks me. “You should, it’s good for you”.

A February Sunday’s report begins in a Brooklyn hangar and ends in a small airport North of New York. In between lay five hours of shooting that pass quickly while he goes back and forth from a trailer, silent and reserved, cigarette in mouth, no shoes on (he feels comfortable barefoot), in his hand – the typical wooden cup of mate, a very popular drink in South America. “Do you drink it too?” he asks me. “You should, it’s good for you”.

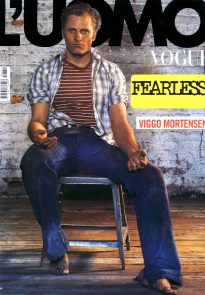

I have the chance to observe him for a long while: before the camera he’s extremely focused, each time his green-blue glance paints a palette of different emotions, his mouth hardly ever opens into a smile. That Viggo Mortensen has charisma, and a shy almost intimidating attitude, is a fact. He doesn’t talk much, but then, you discover that what he says is never banal, and you like his honest, open approach, with no trace of hamming or star-like behaviour. He’s not prone to easy and predictable enthusiasms, but a thirty minute chat in the car is enough to understand how diverse, all-comprising, and exciting his interests are.

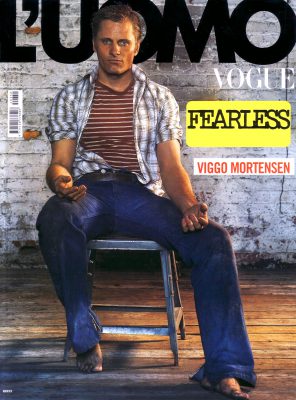

Viggo Mortensen, appointed to super stardom by critics and audiences after the triumphant success of The Lord of The Rings epic trilogy (whose last installment won 11 Academy Awards) is not just an actor with a filmography of over 30 movies, counting a range of roles that space from the now legendary Aragorn, the sensitive and romantic king-warrior of J.R.R. Tolkien’s trilogy, to Gwyneth Paltrow’s lover with no scruples in The Perfect Murder, the tormented Vietnam veteran in The Indian Runner, and the bucolic Amish in The Witness.

What makes him a character of his own in the world of Hollywood are his various other activities, which he cultivates with just as much commitment and passion. He’s indeed also a painter, writer, photographer, poet and musician; exhibitions of his works have been held in galleries around the world and his books and CDs have been released by a small publishing company, Perceval Press, that he founded in order to give voice to independent ideas and personalities.

Sometimes he finds inspiration to experiment in new means of expression in the very movie set experiences, which intrigue him and make him curious. For instance, he tells me that his latest movie Hidalgo – “Ocean of fire” (out in March in the USA, and this month in Italy too) partly inspired his recent photography book, Miyelo. “It’s kind of funny,” he says with a little irony, “I find myself having spent most of my time talking about movies, instead of making one. Tonight I am leaving for Toronto, I don’t know where I’ll be off the next day, have a look at the list of cities where they’re waiting for me”, he says, showing me the promotional tour schedule for the Touchstone/Disney colossal. “Anyway, it’s part of my job, the secret is managing to always have a positive attitude: if you’re doing something that’s not properly your thing, you’d better do it well and perhaps try to make it interesting. Complaining would be useless and hypocritical”, he states with no beating about the bush and solid realism.

Now let us give a look at this Western directed by Joe Johnston, based on a true story in which Viggo is Frank T. Hopkins, an adventurous and courageous cowboy–with Indian blood–who’s invited by a sheikh (Omar Sharif) to test his Mustang Hidalgo in the Ocean of Fire, the famous tough 3000 mile race in the heart of the Arabian desert, against well experienced Bedouin riders.

“We’re at the end of the nineteenth century, at the end of the romantic idea of the Wild West,” the actor explains. “The railway had reached the meadows, and I liked the fact that my character sets out for the East, right in the opposite direction. His journey is an ordeal but it is also a journey of individual redemption, a journey into self-knowledge and knowledge of other peoples. And he does not approach it with the attitude of a conqueror, he does not give orders and advice, in the American style,” he points out revealing his liberal pacifistic faith.

“Besides, I am satisfied that the movie has treated the Arab and Native American culture with dignity and respect.”

Viggo himself, a passionate advocate of civil and human rights, while shooting in South Dakota was so impressed by an Indian ritual dance, the Ghost Dance, that he decided to frame it in 13 stills, “that is, with only one film” he states, “using a panoramic camera, as suggested by my friend Richard Cartwright, the movie’s still photographer.

The dance features twice in the movie,” he continues, “the first time at Wounded Knee Creek, where one of the most violent massacres in Native American history took place, the second, in the form of an hallucination that my character has in the desert, during the race. I tried to capture that moment — I was very surprised by how seriously and carefully the tribe’s members prepared to re-enact a page of their past — as respectfully as possible. To me, it is the recreation of a dual event: a more recent one that took place during the shooting, and an ancient one, that took place in 1890.”

That’s why his images have an ethereal almost surreal quality, on the border between dream and rapture: together with literary and poetic texts they gave life to a book of great visual and emotional impact, Miyelo, and have also been exhibited in a gallery in Los Angeles.

To educate the public, to move people, but above all in order not to forget: here’s the reason behind this publication, which not only testifies his interest in minorities that suffer vexation, injustice and violence, but also reveals a personal commitment.

He tells me that after wrapping the movie he went back to South Dakota to take part in the Big Foot Ride, a ceremony that commemorates the victims of the massacre and, as soon as our car arrives at the airport, I watch him enter an internet station to print out the interview in The Native Voice Media, in which he spoke about the event.

“Here, you may find it interesting,” he says, handing the pages to me. “I was very honoured to take part in such an event. And taking pictures of the Ghost Dance was one of life’s lucky moments.”

I myself can say, that I am having a lucky moment, because the 45-year-old man standing in front of me asks me to keep him company while he waits for his flight; he’s comfortable talking about various issues, and it’s impressive to see how really authentic he is. So we talk about the exhibitions he’s just seen in New York – David Armstrong, Joel Sternfeld, Picabia – about the flamenco show with Sara Baras that he luckily got the chance to see the night before, and about his passion for photography, which goes back to the years of his adolescence.

I discover that he understands Italian (he also speaks perfect Danish, his father’s mother tongue, and Spanish, because he grew up in Argentina and Venezuela) and that he reads a variety of American and European newspapers, because he’s always looking for a critical information analysis. I am impressed by a certain reluctance he shows in letting the driver help him with his luggage: he notices, and whispers to me in a serious tone:

“I want to remain a normal person, which also implies carrying my own bags and doing my laundry.” Yet, the unconventional star gets promptly recognised by the passengers in the small airport’s waiting room, and as he patiently signs a few autographs, he tells me that while he’s planning to set up a studio in his garage, at home in Venice, California, he paints in the kitchen, with his canvases on the floor, but when inspiration comes, any place is a good place (while shooting The Lord of The Rings in New Zealand, he would often travel by car searching for locations); he tells me that a bag with all his notes for a book of poetry and short stories just got stolen – “…the work of three years, practically gone” – and on the personal level, he confesses that only for his son Henry (born from his relationship with the punk singer Exene Cervenka) does he feel the most unconditional love possible.

I look at my watch, the flight is about to be announced. Viggo starts rummaging into a duffle bag and gives me one of his CDs, Pandemoniumfromamerica, released in collaboration with the guitar virtuoso Buckethead — a suggestive explosion of sounds and lyrics — and a book he published at Perceval Press, Twilight of Empire — a collection of various “non-aligned” opinions and reports on occupation in Iraq. Then he says goodbye and disappears behind a glass door. On my way home, I think about something he told me at the beginning of our conversation: “Learning is what makes life worth living.”

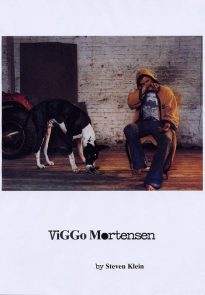

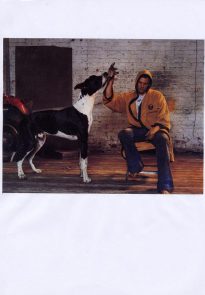

Images

Cover scan by ViggoMakesMe.HormonalAsHell, full-page interior scans by sachie. Source of detail images is unknown.