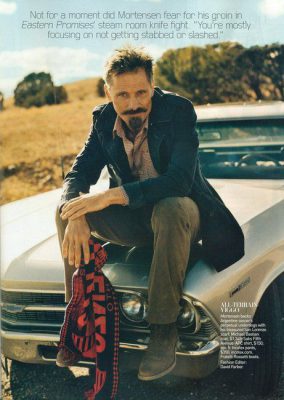

Though he was born in New York City, the Argentine soccer-fan scarf looped around his neck immediately flags Mortensen’s affinity for the great elsewhere–his favorite team (somehow unsurprisingly) is San Lorenzo, by tradition Argentina’s underdogs. Before they divorced when he was 11, his American mother and Danish father trooped their three boys (Viggo’s the eldest) through Argentina, Venezuela, and Denmark, where his father managed farms. Viggo’s handy too–he can cook, do laundry, mend his shirts and whatnot. He spends quite a bit of time with his parents; his father is now pretty much retired and lives on a farm. Like the father in The Road, Viggo has an outdoorsman’s self-sufficiency. “I’d like to learn more about how to fix engines,” he says. “I have a 1948 pickup truck, and that’s a very simple engine. But today, I think you need to be some kind of specialist.”

Before the stage scooped him up, he sold flowers on the street, moved furniture, was a longshoreman. It has always helped that he looks like a Round Table knight; parts abound for the handsome hero-rescuer waving a literal or metaphorical sword. In the business, he’s that worldly poetic soul who can do credible justice to gangland Russian, Sioux, or Elvish dialects. That guy who looks great on a horse. That guy who never kills anyone who doesn’t need killing.

In David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence, he is Tom Stall, an upstanding family man who has somehow, somewhere learned to break a man as easily as he pours him a cup of coffee at his diner. Called back from the reserves to star in Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises, Mortensen is Nikolai the chauffeur, whose tattoos advertise a moderately successful, mid-level career in the Russian mafia while the wraparound shades mask surprising humanitarian impulses. The Russian underworld types he found to school him in their ways finally relaxed “once they realized I wasn’t going to make fun of them,” he says.

He also went for a walkabout in the Urals. “We kind of worried he’d never come back and we’d never find out what happened to him, until we’d probably find him running the country eventually,” says Cronenberg, who insists Mortensen “takes the best out of Method and leaves the bullshit behind.” As Aragorn, a caped crusader in The Lord of the Rings trilogy, he supposedly slept for weeks in his medieval getup. Cronenberg suggests this had less to do with any Methodmania (as was conjectured) than it was an attempt to render the costume less obviously a costume. On the set of Eastern Promises, Mortensen had wanted to wear Nikolai’s shoes around, break them in so they’d look right. Feel right.

Nikolai’s charming nickname is “The Undertaker.” Around the set, his squared-off Dracula pompadour acquired a nickname, too: “The Soviet Bloc.” In shooting the now classic naked knife fight in a public bathhouse, Mortensen says he could only hope everyone would heed the exquisitely timed choreography. Not for a moment did he fear for his groin, he insists. “You’re mostly focusing on not getting stabbed or slashed.”

Preparing to clip off a murder victim’s fingertips as if he were deadheading a rosebush, Nikolai extinguishes his cigarette on his own tongue. That was Mortensen’s idea–and there were multiple takes, so he was obliged to do it over and over again. “Well, that’s the cost of coming up with something neat like that,” says Cronenberg. In this age of DVD screen captures, Mortensen volunteered to lose the towel for the steam-bath knife fight, which was not actually demanded by the script. “To suddenly get coy about it, and have things blocking his crotch”–as if Nikolai were some mafioso Austin Powers with better biceps and bone structure–“would have been ridiculous,” Cronenberg says.

Mortensen’s back kicked out the day before the scene was to be shot–for the first time ever–but he never mentioned it. He didn’t need attending to like some high-strung racehorse, requiring a masseuse on the set or heat treatments between takes or anything of the sort. For treating improv as extreme sport, Mortensen surely deserved more than the critics’ unanimous acclaim, even if he confesses he’s a little turned off by the hysterical shrieking run-up to the Academy Awards. Three nominations–one for a Golden Globe, one for a Screen Actors Guild award, and, finally, the Oscar nod itself–are possibly a harbinger of something. Or possibly a harbinger of nothing.