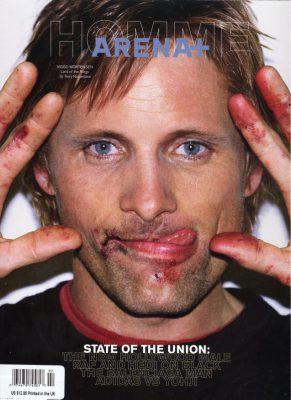

As crass and stupid as Hollywood might often be, we should give it credit for this: sometimes it gets it right in the end. It may have taken the best part of 20 years to figure out quite what to do with Viggo Mortensen, but the important thing is that the wait is over. One role is all it took—Aragorn, the valiant, rightful claimant to the throne of Gondor in Peter Jackson’s suitably epic Lord Of The Rings movie trilogy. Eyes ablaze and sword aglint, Mortensen proved a captivating warrior who stirred the hearts, souls and in many cases the loins of the first blockbuster film’s audiences. The very first moment he is glimpsed—silently sitting in the shadows inside the Prancing Pony inn, his eyes shielded by the hood of his cloak—signalled the arrival of a New Hollywood Hero, a dynamic man of mystery, action and romance. Tall, graceful, handsome, athletic, charismatic—these are qualities that Mortensen has always possessed, but before this had never projected them with such vigour. The studios responded with a ripple of recognition. Here was the magic formula that represents the holy grail of the movie industry, namely the bankable leading man. Viggo had truly arrived.

As crass and stupid as Hollywood might often be, we should give it credit for this: sometimes it gets it right in the end. It may have taken the best part of 20 years to figure out quite what to do with Viggo Mortensen, but the important thing is that the wait is over. One role is all it took—Aragorn, the valiant, rightful claimant to the throne of Gondor in Peter Jackson’s suitably epic Lord Of The Rings movie trilogy. Eyes ablaze and sword aglint, Mortensen proved a captivating warrior who stirred the hearts, souls and in many cases the loins of the first blockbuster film’s audiences. The very first moment he is glimpsed—silently sitting in the shadows inside the Prancing Pony inn, his eyes shielded by the hood of his cloak—signalled the arrival of a New Hollywood Hero, a dynamic man of mystery, action and romance. Tall, graceful, handsome, athletic, charismatic—these are qualities that Mortensen has always possessed, but before this had never projected them with such vigour. The studios responded with a ripple of recognition. Here was the magic formula that represents the holy grail of the movie industry, namely the bankable leading man. Viggo had truly arrived.

“There is only one kind of actor, and that’s a supporting actor. In a movie, you’re raw material, just a hue of some colour and the director makes the painting.”

Those of us who waste our lives pondering exactly how the Hollywood machine works were not at all surprised earlier this year to discover what Mortensen was doing next. Disney had swooped on the belatedly hot star to take the lead role in its $50 million historical action adventure romance Hidalgo, a true story of courage, endurance horse riding and exotic locations. There is a very short list of actors with the swashbuckling movie star magnetism to convince in this type of project—Brad Pitt, Russell Crowe, Hugh Jackman—and at any given time there are numerous projects competing for this elite roster’s attention. After Aragorn, Viggo has ascended to the pantheon. Newly anointed as the coolest, sexiest, prettiest star, he has the world—or at least every chequebook-waving studio—at his feet.

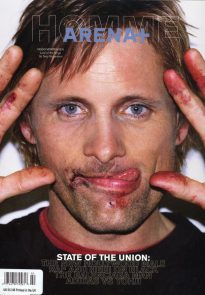

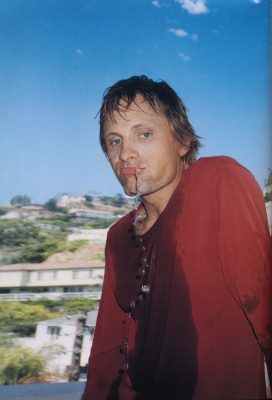

Not that you’d guess from talking to him, mind you. Taking a break from our photographer Terry Richardson’s cameras, he turns in an instant from goofy performer to pensive interview subject, the very essence of quiet self-effacement. He takes compliments graciously, before deflecting, undermining, rebutting. “I’ve been around a long time,” he begins. “I’ve been told that I’ve arrived—or, presumably, left—many times over the years so I take it with a grain of salt.” He does concede that “it’s a relatively new situation obviously”, adding: “but if it all went up in smoke tomorrow, I wouldn’t really care that much. There are a lot of things that interest me. I’m doing the best I can. As for my fortunes, it’s really a crap shoot.” However excited we may be about the opportunity that’s now within his grasp, for Viggo, too much focus on career strategy can be self-defeating. “I think that people who get to a certain position, and then try to ferociously defend it or build on it, it’s kind of a dead-end street,” he says. “You see people becoming miserable that way.”

Viggo Mortensen will be 44 on October 20. He has made 38 movies. Among the ones you may have seen are thrillers Carlito’s Way and Crimson Tide, Jan Campion’s literary adaptation The Portrait Of A Lady, Kevin Spacey’s directorial debut Albino Alligator, Gus Van Sant’s Psycho remake, Sandra Bullock’s rehab comedy 28 Days and of course The Fellowship of the Ring. His most remarkable, heartbreaking performance was in The Indian Runner, directed by Sean Penn in 1991, in which he plays a Vietnam vet who self-destructs despite good intentions and the healing love of Patricia Arquette. He was powerful as the psychotic Master Chief who brutalises Navy SEAL Demi Moore in GI Jane. And he slamdunked his twin ‘sexy bohemian’ movies A Perfect Murder and A Walk On The Moon, playing respectively an artist and a travelling blouse salesman who understandably causes married beauties Gwyneth Paltrow and Diane Lane to lose their heads and their virtue.

Viggo Mortensen will be 44 on October 20. He has made 38 movies. Among the ones you may have seen are thrillers Carlito’s Way and Crimson Tide, Jan Campion’s literary adaptation The Portrait Of A Lady, Kevin Spacey’s directorial debut Albino Alligator, Gus Van Sant’s Psycho remake, Sandra Bullock’s rehab comedy 28 Days and of course The Fellowship of the Ring. His most remarkable, heartbreaking performance was in The Indian Runner, directed by Sean Penn in 1991, in which he plays a Vietnam vet who self-destructs despite good intentions and the healing love of Patricia Arquette. He was powerful as the psychotic Master Chief who brutalises Navy SEAL Demi Moore in GI Jane. And he slamdunked his twin ‘sexy bohemian’ movies A Perfect Murder and A Walk On The Moon, playing respectively an artist and a travelling blouse salesman who understandably causes married beauties Gwyneth Paltrow and Diane Lane to lose their heads and their virtue.

There’s an apparent randomness to all of the above, although in truth Mortensen’s career was both cohering and hotting up when his seemingly miraculous lucky break occurred. In the role of Aragorn, Peter Jackson had cast pretty, young Irish actor Stuart Townsend, and two weeks’ shooting on the trilogy had already occurred before the director and star realised it just wasn’t working. A replacement was needed, and fast. Viggo got the call; would he be willing to fly to New Zealand tomorrow for a year or so’s filming? The request flew in the face of all the actor’s instincts about preparation being the essence of truthful performance. He hadn’t read the book. It would mean being apart from his son Henry, who he cares for jointly with musician ex-wife Exene Cervenka (formerly of punk band X). But Henry told him this was way too cool a thing to turn down, and Viggo was on his way.

Today the actor dismisses some of the wilder tales about his immersion in his character as his co-stars’ exaggeration, but to Jackson he will forever be his ‘miracle man’. Says producer Mark Ordesky: “You look at him on camera and think, ‘Who else could be Aragorn? Who else could be the brooding man of action—dark and edgy but with a soul?'” And, let’s not forget, romantic. The small but perfectly formed love story, in which Liv Tyler’s elf Arwen gives up her immortality to be with her beloved mortal Aragorn, is a tender highlight. Jackson, revealing a sure instinct for delivering big emotional moments with simple economy, repeatedly allows his camera to be sucked in by Viggo’s brightly intense blue-green eyes.

Some might be surprised that we are trumpeting a newly minted movie star who left his twenties a long time ago, but in truth the rules for men and women in Hollywood are vastly different. Russell Crowe was 36 when he swung his sword in Gladiator. Hugh Jackman was a mature-looking 31 when he landed the dream assignment of Wolverine in X-Men. Eric Bana, catapulted from indie flick Chopper to upcoming action blockbuster The Hulk, is 34. It’s perhaps no coincidence that all three of these stars happily honed their craft in their native Australia away from the global spotlight, before the right role came along to give them their belated international breakthrough. Like Mortensen, we never knew these actors as boys, so we have no problem believing in them as men.

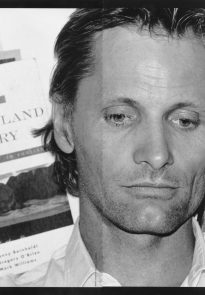

Mortensen would be the last person who would ever volunteer information on his burgeoning fame, but under interrogation concedes that since The Lord of the Rings his life has changed. People magazine included him among its most recent “50 Most Beautiful” list, an accolade that pleased his mother but for him is “just another strange thing that’s happened to me that’s come and gone.” He notes wryly: “I guess they’re not going to sell magazines by doing Manchester’s loveliest plumbers, although you could make a case for them I’m sure.” He talks about a recent poetry reading and book signing at a Santa Monica independent bookstore, at which people from diverse destinations such as Japan, Germany, Canada and New Zealand queued around the block in hot sunshine for up to ten hours. “This would never have happened a year ago,” he says, not with vanity, but with mild bewilderment. “I started signing books at 8.30pm and I didn’t get out of there until 1.30 in the morning.”

He still gets “an unbelievable amount—at least it’s incredible to me” of fan mail, which is now beginning to take its toll. “I’ve done my best to answer it, but I can’t do that any more,” he sighs. “It deprives me of too much time, to sleep or to make things.” Earlier, he’d called his life “pretty chaotic”, adding “I definitely need to sleep more. But as they say, you can sleep when you’re dead.” Now we have a whole new take on that comment: a vision of Viggo, working through the night, servicing his world community of fans. Regretfully, he says in future he’ll only have time for people he physically encounters in the street, or who come to his performances and signings.

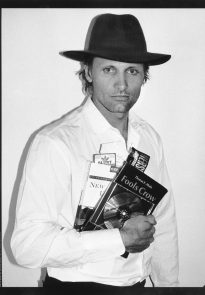

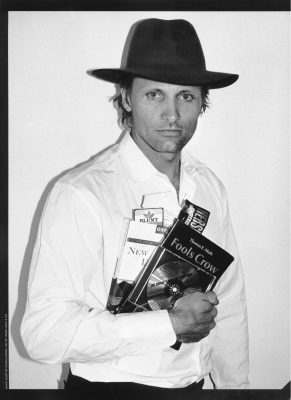

With characteristic understatement, Mortensen remarks that in addition to acting “I do other things.” Indeed. Painting, photography, jazz music, poetry. Not in a dilettante, movie star way, but in a serious, productive way. Four collections of art and photography published under the titles Signlanguage, Coincidence of Memory, Recent Forgeries and Hole in the Sun. Several CDs of music and poetry, including Don’t Tell Me What To Do and One Less Thing To Worry About. And now his own publishing company, Perceval Press, which will exploit interest in his own output and provide a platform for neglected artists from places such as Cuba.

With characteristic understatement, Mortensen remarks that in addition to acting “I do other things.” Indeed. Painting, photography, jazz music, poetry. Not in a dilettante, movie star way, but in a serious, productive way. Four collections of art and photography published under the titles Signlanguage, Coincidence of Memory, Recent Forgeries and Hole in the Sun. Several CDs of music and poetry, including Don’t Tell Me What To Do and One Less Thing To Worry About. And now his own publishing company, Perceval Press, which will exploit interest in his own output and provide a platform for neglected artists from places such as Cuba.

Mortensen isn’t prone to bouts of introspection, but the way he talks about the world provides enough clues to what’s going on inside his head. Take this piece of proud-father speak, in relation to 14 year old Henry—”He’s got a great mind, and very perceptive, and really really creative and an inspiration to me all the time.” You don’t need to be Sigmund Freud to divine which human qualities Viggo particularly esteems.

Here are some other things he does reveal. He spends a lot of time on his own, and with Henry, who as a child took small roles in a couple of Viggo’s films. When Exene was on tour “we spent the last few months together every day.” In his own childhood, Viggo and his family (Danish dad, American mum) travelled a lot, bobbing between Denmark, Venezuela and Argentina, before settling in the States aged 11. “You tend to find there are a lot of actors that have had that itinerant, nomadic upbringing,” he reflects. “Just the fact that a restlessness was almost bred into the person.” A picture builds up of a life lived as a series of rare and celebrated moments. “Last week we were filming Hidalgo in High Plains, Montana, where there was no fence for miles; you could just imagine that it was 1890 or 1790,” he says. “I was in the middle of a herd of six or seven hundred horses. I was really aware of the fact that very few people would ever get to be in such a place. Nobody in the world gets to be in the middle of that many horses, running as fast as you can.” And where does that thought lead you to, I ask. He pauses. “Just, ‘Don’t forget this’.”

Mortensen has a poetic take on almost any topic, even one as mundane as the shooting of a movie. “It’s like an ancient ritual,” he says, “where you sow the seeds, you set up the circumstances, the vestments, the wardrobe, the equipment, the cameras, the lights. And you have the words for the ceremony, you have the actions, the gestures that have to be performed, and then it takes on a life of its own. You hope for some good luck, you hope the gods are with you and your crew and that something magic happens.” This account doesn’t really square with the actual experience, which involves hours of sitting around bored while the director huddles with crew members, and then you deliver one line 14 times and they print the one where your concentration wavered but the dog hit his mark—but we’re grateful that Viggo sees life differently.

“You tend to find there are a lot of actors that have had that itinerant, nomadic upbringing—just the fact that a restlessness was almost bred into the person.”

Right now, he’s having a ball playing Frank Hopkins, the real-life scout, hunter and cavalry despatch rider who found fame in the late nineteenth century in the US for winning a series of long-distance endurance horse races, becoming part of Buffalo Bill’s legendary Wild West Show. Finding him and his steed billed by the showman as ‘Hidalgo and Rough-Riding Frank Hopkins, the greatest endurance racing team the world has ever known’, his life turns when an emissary from an Arab sheikh challenges that to live up to that title he must compete in the sport’s real premier event, a 3,000-mile race through the Arabian Desert. Once again, the qualities that attracted Mortensen to the project are telling. First, its respectful depiction of the Native American Lakota people, whose mustang horses—dismissed as ‘stubby Indian ponies’—Hopkins rides. Second, that despite its blockbuster family-film aspirations, the Indian and Arab characters speak in their own language with subtitles, not in English. And third, and most importantly, “What I like about it is that this American goes overseas, not as in so many Hollywood movies, not to teach people anything, not to educate them, not to bring them up to speed about the American way, but he goes over there just to do what he can, with an open mind. And I hope, like the audience, he learns something about that place, the people, the animals, and as a result of doing so he learns about himself.”

Throughout an hour of conversation, these themes are woven into the fabric of every thought: an open mind; humility; doing your best; a constant quest to learn and enrich your life. “There is only one kind of actor, and that’s a supporting actor,” he says, meaning that even in a lead role you are always supporting the vision of the director. “In a movie, you’re raw material, just a hue of some colour and the director makes the painting.” He’s come to accept, and respect, the order of things. “I’m eternally anxious about doing the job right,” he says. “Not in a way that paralyses me, but just like ‘Oh shit, you could do that better’.”

Terry’s anxious to get to the second leg of the shoot, but Viggo’s still communicating his philosophy. “If you’re working, you should be thinking,” he says. “If you make the effort to be actively involved in your work and your life, you’re bound to learn something, one way or another.”

One final thought. “I’ve said this before, but I don’t know if they used it. Robert Louis Stevenson said, ‘To travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive. And a true success is to labour’.”

That’s your motto, Viggo, that’s how you live your life? “Yeah,” he says, “but I don’t always remember it.”

Scans by Lilith, whose Viggo Mortensen website is one of the dear departed. We miss you, Lilith. Except for p 5. Not sure where I found that.